Clik here to view.

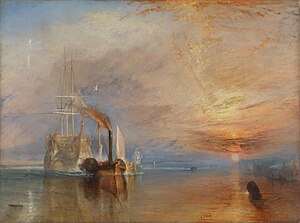

The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last Berth to be broken up (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 19th September 2013

In 2005 listeners to BBC Radio 4′s The Today Program (the flagship morning news broadcast) voted William Turner’s masterpiece, The Fighting Temeraire as Britain’s favourite painting. And viewed from a 21st Century perspective it is easy to see why. Hindsight is a great imbuer of symbolism and The Fighting Temeraire can seem to speak from the past to our collective view of a Britain resonant with loss and decline.

The great fighting Battleship, heroic in action at Trafalgar, is pulled on the final leg of her final voyage toward the breakers yard in Rotherhithe, East London, the victim of advancing Maritime technology; an ignominious and anonymous end for so great a vessel. In the background, Turner’s trademark, an epic, flaming, setting sun, a vivid reminder at the last of this ships glories and a mournful farewell to this mighty beast whose exploits on the bounding main have, to quote Shakespeare ‘bestrid the oceans’. At her bow, a small soot-bellowing tug, dark and incongruous, represents, I think, a future tinged with fear. The ugliness of the industrial age encroaches unbecomingly on the solemn passing of a golden generation.

Turner’s painting marks the passing of a redundant technology with quiet, tender sadness, infusing the death-white leviathan with the shadow’s of burning brilliance and the qualities of humanity. The Temeraire was a “fighting” ship and her exploits were great, blazing in battle as a setting sun blazes. There is sadness too that she cannot blaze at her last as she blazed in her prime. Echo’s too, then, to a Twentieth Century Eye, of Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that goodnight; old age should burn and rage at close of day.”

Only now, at her passing, she seems already to be a ghost, her pale, shadowless form having surrendered its colour and vitality to the setting sun, which, perhaps intentionally imbues the sky with her bumblebee battle colours, a final reminder of a life which was lived out in colour.

The contrast with the smaller, dirtier, industrial era paddle steamer tug at her bow speaks of a diminution of the generations that follow without her. And yet we have to remember that Turner recorded this moment in 1838, before the Industrial Revolution had reached its zenith, before the full range of its ugliness had become apparent. If Turner’s painting speaks to us of a collective diminution in the wake of a great generation it is because his painting represents universal morning that death robs us of life’s vitality and a fear that with each passing generation something is lost that cannot be regained.

And yet Turner has redeemed the Fighting Temeraire as no rendering of her in full sail, bounding toward the French could have done. The actor, Richard Burton, once remarked that the only interesting male characters are those who are defeated men. And just as Arthur Miller‘s Willy Loman, or Shakespeare’s Anthony or Lear are able in their defeat and degradation to gift us poignancy, and insight, so that, at her last, Temeraire is redeemed by Turner, her final moments afforded a grandeur and drama that the lower Thames Estuary seldom affords visitors: so that at her last she is preserved as the Fighting Temeraire

The Musings of James Bond

The Fighting Temeraire is probably Turner’s most famous painting and certainly his most accessible, speaking directly to the viewer across the ages in a way that some of his paintings of Venice and London cannot. I am no aficionado of James Bond, but was surprised to find that it makes a brief cameo in the latest incarnation of that film franchise, as Bond muses on the inevitable decline of one generation in the face of another.

I might be wrong, but I would hazard that Turner’s masterpiece stands alone in the pantheon of British Art which has made its way into James Bond Films. Perhaps there is a reflective moment in an earlier film where Roger Moore contemplates the passing of the rural idyll as captured in Constable’s The Hay Wain but if there is, I cannot recall it.

Yet something else struck me about Temeraire‘s cameo appearance alongside Bond. The film (Skyfall) seems to concern itself with loss and decay in ways I had not personally anticipated, and the scene in the National Portrait Gallery forms part of an underlying theme within the film on both national and personal decline.

The symbolism within the film is clear, Temeraire and Bond are both once-great British warriors and Icons facing the Breakers yard. That Bond, by the film’s end, has faced off his demons and lives on to fight further celluloid villains is perhaps fitting, for the very resonance of The Fighting Temeraire comes from the knowledge that she can never return, that her glories are past.

Of course, we invest in ships, qualities of humanity that we deny other technologies and it is wrong to assume that this ended with the passing of the wooden ships. Testimony from sailors on the warships of WWII is as fond as that of the preceding generations. Lancashire cotton Mills, Clydeside Shipyards or Salford Foundries are as elemental to our recent folk memory as “following the sea” once was and yet if anything, we invest in them inhuman qualities of absence such as Facelessness, Godlessness and Beastliness. The cramped conditions of slum dwellings were little different from the conditions of a fully crewed Gun Deck and the immoral behaviour which so concerned Victorian society when contemplating the northern cities, would have shocked few who witnessed the mass shore leave of a boat full of “Jack Tar’s”.

And yet, though HMS Temeraire was, on one level, no more than a mobile platform for gunnery and on another, a faceless machine for Geopolitical Power Projection, her passing, like the passing of all great warships, carries with it a sadness which can only be measured in human terms.

In a box somewhere in my mother’s house, lies a small metal tin which once belonged to, a sailor of the Second World War.

The box, or rather its contents are a touching testament to the itinerant life of a sailor, containing as it does a paltry collection of keepsakes that represented the sum of his belongings between 1932 when he joined the Navy and 1947, when he was decommissioned. A newspaper cutting showing a photograph of the landscape of home, some family photographs and some old foreign coins are not much to show for such a long time at sea. There is a subsequently added box of medals of course. detailing the theatres in which he fought.

Yet as interesting to me are his cap ribbons or “Tally’s“, bearing the names of each of the ships upon which he served. These bear witness to more than the mere fact that these ships once existed, that he once stood on their decks, or lay in hammocks within their guts. They are all that remains to remind us of days and weeks and months of lives led, of company kept, of friendships formed of petty feuds or shared jokes or fears. Those slender black and gold ribbons witnessed long periods of boredom, of thoughts of home or of mealtimes or rum rations, and short moments of unyielding, stomach clenching terror and fear. The men, or most of them, have passed from the earth and of the ships themselves, there is little left. Only two still exist in the form one would deem recognizable. The rest having long ago gone the way of Temeraire in the breakers yard.

HMS Hereward lies somewhere of the coast of Crete, her gunnel’s and heads now the redoubt of fish and anemones.

And then there is HMS Victory. No, my sailor of the 2nd World War was not also a contemporary of Nelson. But unlike Temeraire, as flagship at Trafalgar, HMS Victory has been afforded a special status and remains to this day a serving (albeit ceremonial) warship, the flagship of the First Sea-lord.

At first the presence of Tally’s for HMS Victory confused me but it appears that Sailors who are injured or based on land in Portsmouth for a time, served and continue to serve aboard her and salute returning warships as they enter Portsmouth Harbour. My Grandfather was, at one time or another, one of them.

On the last day of my summer holidays, in late July, I took my mother and my nephew to Portsmouth Historic Naval Dockyard for the day. Partly, this was an excuse to spend time with my nephew, of whom I see little, and partly this was in order to satisfy my own boyish interest in big warships and an unrealized dream of swashbuckling derring-do, in the manner of Errol Flynn or Burt Lancaster. And then there was curiosity as to why my Grandpa should have found himself serving on HMS Victory.

The young rating who explained this to me looked so young that she could have been my nephews older sister and I left feeling an impossible warmth for the Navy and for the ship and the country Victory defended and defends still.

And I left too, with the melancholy of loss in my mind, perhaps feeling a greater understanding of Turner’s painting than I had previously felt. For, perhaps unintentionally, Portsmouth Naval Dockyard tells a sad story resonant with absence.

That is not how it presents itself, of course. It is clear from the various brochures we picked up that day, that it remains a potent recruiting tool for the hearts, minds and career ambitions of Britain’s young. Alongside the old warships are activity centres designed to demonstrate the action packed life of adventure a career in the navy can provide. If not exactly cutlass battles for the honour of Olivia de Havilland, then certainly something which would be preferable to a wet Tuesday in French class.

The Elephant in the Room

Yet, there is, in Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, a great historical absence; a vast Elephant in the Room which no one mentions. Taken as a timeline, the Mary Rose, HMS Victory and HMS Warrior, represent the progression of England’s, (and then The United Kingdom’s) rise to global prominence from the position of a moderate European power to Global Hegemony.

We can track this rise through the development of naval technology. Mary Rose existed at a time when the dominant means of victory at sea was through the boarding and capture of an enemy ship. Consequently her design was top-heavy, featuring a high, prominent Forecastle allowing archers and cutlass or pike wielding boarding parties the purchase and height needed to inflict damage on an enemy crew.

By the time Victory led Britain to that decisive victory at Trafalgar and heralded the start of the Pax Britannica, (a century of Global Peace ensured by British Naval supremacy), the forecastle had disappeared as the technology of the Cannon had come to represent the dominant means of ensuring victory. Astonishingly, each of Nelson’s First Rate Ships at Trafalgar, carried the equivalent fire-power of the Duke of Wellington‘s entire army at Waterloo. Now the Broadside, not the boarding party was the principal means of ensuring victory, and Nelson’s victory owes as much to the revolutionary tactical deployment of his fleet in the face of this reality as it does to his crew’s superior training and rate of fire.

HMS Warrior, is a product of the Pax Britannica, and a deterrent against potential rivals, was never required to go to war. Victory’s significance lay in her actions. Without HMS Victory, HMS Temeraire and HMS Royal Sovereign or their ilk, there could have been no Trafalgar and British Common Law would likely have given way to the Napoleonic system of the continent in the wake of a cross-channel invasion by the peerless French Army.

Never can a ship have been more aptly named, for the significance of HMS Victory is precisely that she represents triumph; both in battle and as a culmination of the wooden warship as a form of technology. For Trafalgar and the campaign that preceded it was fought in the dying moments of a pre-industrial age and its result and the ensuing peace helped to ensure the very Industrial Revolution which would consign the wooden warship to history.

Within 55 years, Warrior would come to represent a seismic technological leap. Built as a deterrent, she served the role to perfection, never being required to fire a shot. Yet, at heart Warrior is not a culmination as Victory is, but a series of technological innovations that act as a precursor to the next age or battleship design.

Her screw propellers, her large fore & aft mounted guns, her Armour Belt (a thickened, toughened core designed to protect the crucial elements of the ship), and the development of the Bridge as a means by which a commanding officer can direct activities, each represent massive technological advance on Victory. Yet each in turn would quickly give way to further refinement and improvement.

To walk through Warrior is to walk through a transition between modernity and history. As a weapon of war she is efficiency itself, with the below deck areas superbly designed to act as a communal space for sleep, eating and fighting. Viewed against the low ceiling-ed quirkiness and claustrophobia of Victory, Warrior is spaciousness and efficiency itself and yet there remains much that is recognizable, much which is pre-modern and which sets her apart from modern warships. Warrior, is similar in length and displacement to the Royal Navy’s modern Type 45 Destroyer, but closer to Victory in terms of design and utility.

But then what?

And so to the elephant in the room. For something connects the dots between Britain in 1860 the worlds leading and unchallengeable maritime superpower and today. And that something is massive and represents such a seismic advance that it consigns Warrior to the past as efficiently as Victory.

That elephant, giant both figuratively and in reality, was HMS Dreadnought, and her absence is as telling and poignant a piece of history as the touching details of the lives of the men who manned the Mary Rose.

There is good reason why Dreadnought (and indeed, every one of her succeeding class of battleships) is not sitting in Portsmouth or an equivalent British Inlet and it is not merely because she was so massive or so ruinously expensive.

Commissioned in 1860, Warrior was a manifestation of a supremely confident British Navy, and the same can be said of Dreadnought. Indeed, if anything, Dreadnought represented the apex of Royal Naval Dominance in a way that Warrior cannot hope to do.

There is an often told myth that the American Civil War and specifically the Battle of Hampton Roads between the CSS Virginia and the USS Monitor heralded the ironclad age and rendered all other navies obsolete, but this is only true in the sense of their having demonstrated the Iron-Clad’s superiority to wooden warships in battle. Warrior was laid down in 1859, and was the world’s first Iron Built warship.

It is not to decry the significance of Monitor or Virginia to point out that the Iron Age of ships had effectively arrived before they met in Hampton Roads in 1861.

When Warrior was laid down, she rendered existing French, American and indeed, Britain’s own massive fleet of Warships redundant and maintained an easy dominance of the Royal Navy over every other navy in the world. But there was no country called Germany in 1859, and the Empire of Japan was technologically unable, as yet, to manufacture the sort of technology Warrior represented.

Warrior was decommissioned in 1883, after an extraordinarily brief service life of just 23 years, the reason for her decommissioning being that she was by this date, already redundant as a battleship. Coincidentally, Dreadnought would be commissioned 23 years later in 1906, and overnight every other battleship on the planet was rendered obsolete.

Yet Dreadnought was not merely another Warrior. And it was not that Dreadnought reflected a continuation of the Royal Navy’s global dominance (although she did). Dreadnought‘s significance was that she was revolutionary, such was such a massive step forward in the concept of the battleship that no other navy in the world was even contemplating such a leviathan before she was built.

As we have seen, Warrior, represents the transition of all the worlds powers from an age of wooden technology to an age of Iron. Had she not been built, some other nation would have led the way. Dreadnought represented something more essential; a challenge to any aspirant power, a line in the sand, so deep that only nations of real significance could hope to cross it. The brain-child of visionary British Admiral Jackie Fisher, Dreadnought had a purpose that went beyond an arms race. Her intent was to be so powerful that she would end the arms race. She was less of a deterrent to war than a deterrent to build.

In the United Kingdom today there are almost no historic Warships afloat between HMS Warrior (1860) and HMS Belfast (1938), a light cruiser moored upstream of Tower bridge in London, which saw service during WWII, particularly in the Arctic convoys to Murmansk). Why should a Nation so steeped in its long history and in maritime self-image have so catastrophically neglected to preserve a single example of a fighting warship from the years of her undisputed mastery of the Oceans? How could a nation which famously is said to have “acquired an empire in a fit of forgetfulness” have forgotten to preserve a single example of the force that acquired and defended it?

Well, not many nations have.

Only Japan and the United States have preserved examples of the generation of pre-dreadnought battleships that rendered Warrior obsolete.

Mikasa has been preserved because she played a part in the historically significant victory’s over the Imperial Russian fleets at Port Arthur, Yellow Sea and Tsushima during the Russo-Japanese War. Built in Barrow-in-Furness, in Cumbria between 1898 and 1901, she was obsolete before her first refit, thanks to the launch of Dreadnought, but her short period of relevance heralded the arrival of Japan as a significant power and her preservation is an enduring witness to the shock this global realignment forced upon the European powers. To look upon her today is to see something oddly anathema, almost fairy-tale. In looks she is close to the utilitarian ugliness of the modern warship but at the same time she is curiously quirky and individual, as though something of the wooden age had survived or as though she were a creation of one of the anime films her country is so famous for.

USS Texas, is the only surviving contemporary of Mikasa. And like her pre-dreadnought namesake, she is has an incongruity of appearance that is nearly but not quite modern. She is nearly ugly, utilitarian and brutalist as modern warships are, and yet something of the 19th Century hangs over her, an atmosphere that has yet to wholly abandon the romance of the sea.

If surviving pre-dreadnoughts are rare, Dreadnought’s contemporaries and successors are rarer. Indeed, only one survives as a museum piece. And yet, it’s a pearl-er, in many ways a more historically significant Battleship than any since Victory, the USS Missouri, moored off Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

War & the demise of Pax Britannica

For despite the giant leap forward represented by Dreadnought, with hindsight, we can see that her significance, like that of Warrior was less in what she did in battle than what she represented as a statement of Global Power.

Dreadnought took part in World War One as part of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, commanded by Admirals John Jellicoe and David Beattie. She took part in the Battle of Jutland and as such, unlike Warrior, did fire here guns in anger.

Yet, her participation in that battle was as part of a colossal squadron of battleships, whose significance was in their numbers and more importantly the numerical superiority they provided Britain over her German Rival. Dreadnought’s presence at Jutland was important principally because she was one more gun platform which cumulatively deterred Admiral’s Hipper & Sheer from continuing the battle for fear of being on the wrong end of a massacre. Individually she made no difference to the course of the battle one way or the other.

Indeed, the mere fact that just a decade after her construction, she was merely one of a number, tells us all we need to know of her success (or lack thereof) of her deterrent effect. Not only Germany, but every power on the globe was forced to build Dreadnoughts, irrespective of the costs associated. Far from ending the Arms race, Dreadnought hastened it.

Debate continues to rage today about the true significance of HMS Dreadnought. Some argue that Admiral Jackie Fisher made a colossal error of Judgement in having her commissioned, by consigning the Royal Navy to an expensive numbers game which ensured that after the war Britain was unable to contemplate maintaining her previous policy of retaining a fleet of the same strength of the next two navy’s combined. The logic of this argument follows that after agreeing to the Washington Naval Treaty which committed Britain to a parity of Naval power with America and a 5-3 ratio with Japan the Royal Navy could never, hope to maintain command of the seas and could never hope to fight two wars at the same time. Effectively Britain had over-reached and in doing so rendered impossible her continued dominance of the seas and unsustainable, her Maritime Empire.

Consequently, in 1941, with Japan menacing Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaya, the Royal Navy was unable to provide an effective deterrence force to the East for fear of losing the convoy war in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

Others (and I am inclined to agree with this argument), point out that Fisher’s audacious decision to commission Dreadnought represented a brave attempt to end once and for all, what was already a ruinously costly arms race. This argument reminds us that Dreadnought posed a commercial as well as a technological challenge to the world’s navy’s that was entirely in keeping with British Industrial and Naval tradition and which had been proven to have worked in the past.

By changing the minimum requirements for a modern navy, Britain effectively demonstrated commercial as opposed to military muscle, pointing out to potential rivals that in order to compete you would need to match British industrial and fiscal clout against a nation supremely confident to take on all challengers. In 1860 this statement had worked as no power could hope to so challenge the industrial and technological might of Britain.

But by 1906, Britain did have challengers capable, if not of defeating her (Britain’s naval superiority actually increased year on year from the construction of Dreadnought till the Washington Naval Treaty) then of threatening her. In Constructing Dreadnought and then commissioning a colossal warship building program to maintain her advantage, Britain filtered out potential rivals and ensured that no power, be they the US, France, Japan, The Ottoman Empire, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Russia or Germany could match her. Indeed, that Germany was able to devote such colossal effort to Naval expansion, arguably sealed her fate in the war that was to follow by pushing Britain into an unlikely alliance with France and Russia.

In attempting to match Britain, Germany inadvertently set herself a winner-takes-all challenge that she could only win if Britain matched 20th Century Technology with 19th Century naval tactics.

Britain didn’t, and consequently, retained effective control of the seas throughout the conflict.

Blockade, Jellicoe and an under-rated Tactical Mind

At the outbreak of war, Germany expected the Royal Navy to conform to her Nelsonic type and traditions and attempt a close blockade of German Ports as she had done to the French in the Napoleonic Wars. The tactic had worked because the French and Spanish fleets were victims of the revolutionary times, often captained inadequately as a result of political interference and the spirit of “egilte” that led to political appointments, and because the prolonged period sitting idle in French ports damaged navy Moral. When Admiral Villeneuve was finally able to unite his fleet, Nelson could count on the Royal Navy’s superior seamanship and traditions making up for the numerical disadvantage.

German strategic thinking in 1914 counted on the British repeating this strategy (Not unreasonable as the British General Public fully expected this as well). Had she done so, Britain would have been obliged to continuously operate on a reduced capacity of rolling watches dictated to by the finite requirements of coal supply and attrition on Steel Hulls. This would have ensured that the Germans would never have been required to meet the full might of the Royal Navy and could have picked off her fleet until parity of numbers allowed the two fleets to meet on equal terms.

Britain instead adopted a policy of “remote blockade”, retaining a force of destroyers and submarines in the channel while basing the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow in the Orkney’s and deploying Admiral Beattie’s fast Battle Cruisers as an advance reconnaissance force in the Firth of Forth where they could react quickly by seeking out the German High Seas Fleet and making for home as though an isolate squadron of British ships were caught unprotected by Dreadnoughts far from home, lure it towards the Main body of the Grand Fleet. (This was not unlike the strategy of 19th Century Cavalry Tactics deployed by the Large Land Armies of the American Civil War were the likes of J.E. B. Stuart and Nathan Bedford Forrest would maraud independently of their main armies of the field in the hope of gathering intelligence, supplies and damaging the enemy in lightning raids).

This tactic denied Germany the opportunity to pick off the Royal Navy and consigned her to port for most of the war. Even after Jutland, which had proven the German Battleship to be better designed and more robust in protecting the critical magazine component of her warships from flash fire, the High Seas Fleet never again left port to seek out the British.

Yet the real loser of this tactic was the reputation of John Jellicoe, whose skill as an admiral was tested at Jutland, when denied accurate intelligence by Beattie, at the crucial moment, he never-the-less, successfully manoeuvred his massive fleet into the perfect position to give it the decisive advantage over the High-Seas Fleet (a feat all the more remarkable for it’s having been communicated exclusively by flag semaphore. His opposite number pitched a desperate and equally brilliant evasive manoeuvre and escaped in the fading light for home.

In the aftermath of battle Jellicoe was lambasted for failing to destroy the enemy as Nelson had done, but in truth this was a tactical victory, in which Britain held the field at the end of the battle and following which the German Fleet was never to leave port in anger again.

For Jellicoe, the price of victory was his reputation, But for Britain the true cost of victory would only gradually become apparent. For victory in the Naval Arms Race, might have been affordable for Britain had Fisher’s gamble in commissioning Dreadnought worked, but the cost of victory in a World War was not.

The post-war Washington Naval Treaty was designed to limit the half century arms race in Naval technology that had swallowed up Warrior and her successors so quickly, and Britain signed willingly a treaty that effectively ended the Pax Britannica in a way the German High Seas Fleet could not. But it also consigned to history the Royal Navy’s means of commanding the sea. It committed Britain, the US and Japan to a ration of warships of 5-5-3, ending Britain’s long-held naval doctrine of maintaining a fleet at least the same size as her two biggest rivals.

Why?

The Washington Naval Treaty

The answer is that the War and the colossal sacrifice that it required had robbed Britain of the industrial and fiscal predominance required to maintain a navy capable of dominating the globe. Far from being a gesture too far, Dreadnought represented the last time Britain could hope to lay down a challenge to global competitors confident in her ability to back up the challenge with industrial might. The Washington Naval Treaty was willingly signed because a Britain, Bankrupted by the cost of a Global War on land and at sea and war-weary from the sacrifices she had borne was incapable of contemplating the cost of taking on Japan and America in an ongoing arms race.

The Washington Naval Treaty bitterly disappointed the Japanese, but with the hindsight of history, we can see that it was Britain who were the big losers.

Yet this reality was slow to dawn on the British Public who continued until the end of the Second World War to view the Royal Navy as the Guarantor of Britain’s Greatness. Indeed at the time, Britain felt it still ruled the waves. The American fleet was more modern, but was split between the Pacific and Atlantic, and limiting the Japanese fleet to three fifths the size of Britain’s and the French and Italians to two fifths each, must have seemed a lot like their old policy of maintaining parity with the next two fleets combined.

By the outbreak of WWII, Britain’s fleet was largely made up of the most modern elements of her WWI fleet which had survived the culls of the Washington Naval Treaty. Belatedly in the late 1930’s Britain began building a new generation of battle ships (although sticking to the limitations in gun size of the Washington Naval Treaties, as others weren’t).

Yet, with Washington came an unintended consequence, the destruction of the British shipbuilding industry based around a dozen or more ports. Major Shipbuilding centres were still there, by 1939. Glasgow, Belfast, the Tyne, Barrow-in-Furness and The Mersey could still produce ships but a host of skills and trades had been lost. A generation had been idle since the depression with no warship program to sustain the yards in lean times. Moreover, British yards, had not maintained pace with technology and the old rivet building techniques were costly, slow and labour dependent compared with the new industrial techniques.

While Britain’s Battleship fleet grew during WWI it would shrink during WWII as repair of attrition and damages ships, and priority given to transport as well as dependence on Canadian & American-built Convoy Escorts took the place of Battleship Construction.

In contrast to the Pacific Theatre, where Britain’s contribution was non-existent between 1941 and 1945, and minor thereafter, the Mediterranean and Atlantic Theatres, in which the RN was the principal allied belligerent, afforded the battleships a significant role, in large part because the German Pocket Battleships constructed in the 1930’s represented a potent threat as long as they lay in port. Consequently, Names like HMS Hood, HMS Rodney, HMS Warspite, HMS Prince of Wales, HMS Royal Oak, HMS Barham, HMS Repulse and HMS Renown, regardless of their respective fates during the conflict, each carried with them a deal of public affection and regard (and sometimes mourning) throughout the war.

Britain’s limitations as a Global power were better understood by policy makers as hostilities approached as reflected in Naval strategic planning

- The British Quarter of Shanghai was abandoned following Japanese invasion in 1938, left

- Before the commencement of Hostilities with Japan, the decision had been taken that it would not be possible to offer naval support to Hong Kong’s defenders

- While a substantial naval base in Singapore had been developed there was no permanent fleet to defend it and the Formation of Force Z without the originally conceived Aircraft Carrier, represented a token unlikely to deter Japanese aggression.

- Following the fall of Malaya and the defeat of a combined British, Australian and Dutch fleet in the Dutch East Indies The British had no effective Naval force East of Colombo.

- Following Japanese attacks on Ceylon, The Royal Navy withdrew from its base at Colombo to East Africa effectively abandoning the Indian Ocean East of its Oil Supply before 1944.

Despite this, the British public continued, according to Mass Observation, to believe in the navy and in victory as a consequence. And with good reason. While Britain continued to struggle in all theatres before 1942, it was the Royal Navy which provided the only rest-bite, at Cape Matapan, the defence of Malta, the Battle of River Plate, the Evacuations of Greece, Crete, Norway, Dunkirk and Brittany and the sinking of the French fleet at Merse-el-Khabir, the Royal Navy at least was putting up a fight. Even when, as with the sinking of HMS Hood or HMS Royal Oak, the News was a shock to the system, Britain’s navy came thundering back, sinking the Bismark and the Graff Spee.

By the end of the war, the Royal Navy had won in the Mediterranean and Atlantic, largely as a result of a massive expansion in Canada’s Naval contribution, but everywhere else it was clear that the real winners had been the Americans.

USS Missouri & the Pax Americana

Which leads us to USS Missouri. As a ship, Missouri is the supreme manifestation of the Battleship. If we were to draw a line from the Roman and Greek warships through the Viking Long Boats, and onward through the Portuguese Caravels to the Spanish Galleons, and beyond, we would find HMS Victory at the top; the culmination of the Wooden Warship in terms of technology, learned seamanship, endurance, power and achievement.

A similar line through metal warships would be shorter, embracing the first wooden ships clad in Iron and on through Warrior, Mikasa, HMS Dreadnought, Bismark and Yamato. And at the peak of this development would sit Missouri and her sister ships.

Missouri represents the pinnacle not because she was built better or bigger than any competitor but because she represents the end of the line.

When Dreadnought took to the water, she sported guns capable of firing 8” shells. By the time or the Washington Treaty, 16” shells were the least you expected to see from a powerful warship. Missouri topped out at 18” Shells, and was capable of firing them in excess of 20 miles.

This ability led to a change in tactics with Warships obliged to protect themselves from steep falling shells penetrating their decks. When CSS Virginia and USS Monitor had slugged it out to a stalemate in 1861, their firing had little effect, bouncing off the armour. Missouri, required in contrast an Armour belt below the waterline to protect against torpedo’s, armour plated decking to protect against the high trajectories of such long-range shells, and radar and sonar to give advance warning of threats.

Missouri was not the largest battle ship ever to take to the seas. That was Yamato, a ship whose tragic career saw her held back by the Imperial Japanese Navy in the mistaken faith that she would come into her own in a future large naval battle between the big ships.

Having sunk the US Fleet at Pearl Harbour and the British Force Z in the South China Sea with air power alone, the Japanese should have seen that this was a forlorn hope. The advent of the Aircraft carrier ensured that the range war would overtake the big battleship. Formidable as she was, Yamato would eventually be overcome as she was belatedly thrown into the fray by a desperate Japanese Navy. Her passing was in strategic terms as irrelevant as her presence on the Japanese order of battle.

USS Missouri, too was a strategic irrelevance throughout the conflict. While America rocked in 1941 when her battle fleet was decimated in the attack on Pearl Harbour. This might, ironically have hastened America’s Embrace of the Aircraft Carrier as the principal maritime platform and means of conducting and projecting a range war. Had America retained the bulk of her battleship fleet, she may well have suffered greater casualties had this been isolated and sunk on the open sea. Moreover, the incredible shock to the collective American psyche that Pearl Harbour represented was all the greater in the American collective consciousness from the sight of such leviathans as USS Oklahoma and Arizona grounded and smouldering in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbour.

In the harsh terms sometimes demanded by war, the greatest strategic contribution played by the US Battleship fleet in the Pacific theatre was to have been sunk.

And yet the signing of the Japanese surrender was conducted, not on the roomy flight deck of an aircraft carrier, but on the deck of USS Missouri. For all that the Pacific demonstrated American dominance as a global power and represented the final realization that the Battleship had seized to be the most strategically important ship afloat, as a projection of raw power, there remained in 1945, no equal to the battleship.

That Missouri’s career continued until the end of the 20th Century is testament less to her enduring power as weapon of war than to her enduring power as a symbol of Americas military potency. Missouri was refitted to act as a platform for ballistic missiles but her size and the number of crew required to man her meant that she was a supremely expensive luxury in strategic terms. Faced with a world in which surface and submarine based vessels can routinely destroy strategic targets with pinpoint accuracy or where aircraft carriers can project aircraft to attack ships from a range of 500 miles and more, the ability to launch explosive shells in a looping ark for 25 Miles represents an expensive fireworks display, the strategic equivalent of carrying a rifle into a tank battle.

And yet in the final analysis, Missouri has earned her place as the US Navy’s most recent maritime tourist attraction, because like HMS Victory, she represents the culmination of a technological marvel that began with HMS Warrior in 1860. That, she was not afforded the opportunity to flaunt that culmination in a great and iconic victory should not count against her. For in being chosen as the supreme representation of American Power when the flash of a Japanese Pen ushered in the dawn of the American Age on her decks, USS Missouri performed the same function as Victory had in ushering in an age of progress and peace on the waves; a “Pax Americana.”

Decline as absence

And here we return to the Elephantine absence at Portsmouth’s Historic Naval Dockyard, where the story of Britain’s rise and domination of the waves for a century is incomplete. HMS Dreadnought, despite being the last great leap forward and securing British Naval Supremacy for one World War and maintaining her global reach through two, failed to survive the decline in the Royal Navy’s standing that accompanied the Washington Naval Treaty. Moreover, in heralding the final act in the Naval Arms Race which influenced the British into alliance with France and Russia, Dreadnought represents the commencement of the final Act of the Pax Britannica.

Only Great Power’s such as Britain had been could have afforded to maintain so powerful an expression of military technology, and as an economically crippled and war-weary Britain willingly accepted a reduced status in the world, so the supreme embodiment of greatness was deemed too valuable as scrap to be maintained as a museum commemorating a war everyone wanted to forget.

As a deterrent, Dreadnought had failed, despite the supreme triumph that her technology represented. Like Victory and Temeraire, The Dreadnoughts had protected Britain from existential threat and won in battle. Like their predecessors, the Dreadnoughts could not win the war. Only land army’s could have done that but they could have lost it and deserve their share of laurels for securing Britain’s freedom, as a result.

But in the final analysis, Portsmouth’s Naval story is incomplete because only the great can afford the luxury of self aggrandizing history, and the story of Dreadnought, is the story of a great power’s last act of greatness. Dreadnought helped win a war but failed to prevent it and secure the continuation of the Pax Britannica. This turns out to have been her greatest failing and is why her crippled country could not contemplate saving her or her kind for posterity. Without exception, the Dreadnoughts were allowed to go the way of Temeraire. It turns out that we venerate HMS Victory less because of the battle she won, but because of the peace she ensured on Britain’s terms.

Similarly, the military career of a titan like USS Missouri may be what attracts people to visit her, but her true significance and the reason for her preservation lies in her significance as a weapon of peace on the terms best suited to the new maritime oligarch, America.

Time will tell whether an American dockyard comes eventually to offer a home and to make a museum of the USS Carl Vinson or USS Nimitz, those great domineering aircraft carriers who have policed the Pax Americana for my entire lifetime, or whether, with their decommissioning, will come the end of another old sea shanty, and an ignominious destruction in a breakers yard.

Related articles

- The Fighting Temeraire (shubhamvijan.wordpress.com)

- The Fighting Temeraire (professionalartists.wordpress.com)

- Your top ten British masterpieces (paintingsframe2000.wordpress.com)

- World’s ‘largest art show’ kicks off across the UK (itv.com)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.